|

Giochi dell'Oca e di percorso

(by Luigi Ciompi & Adrian Seville) |

|

|

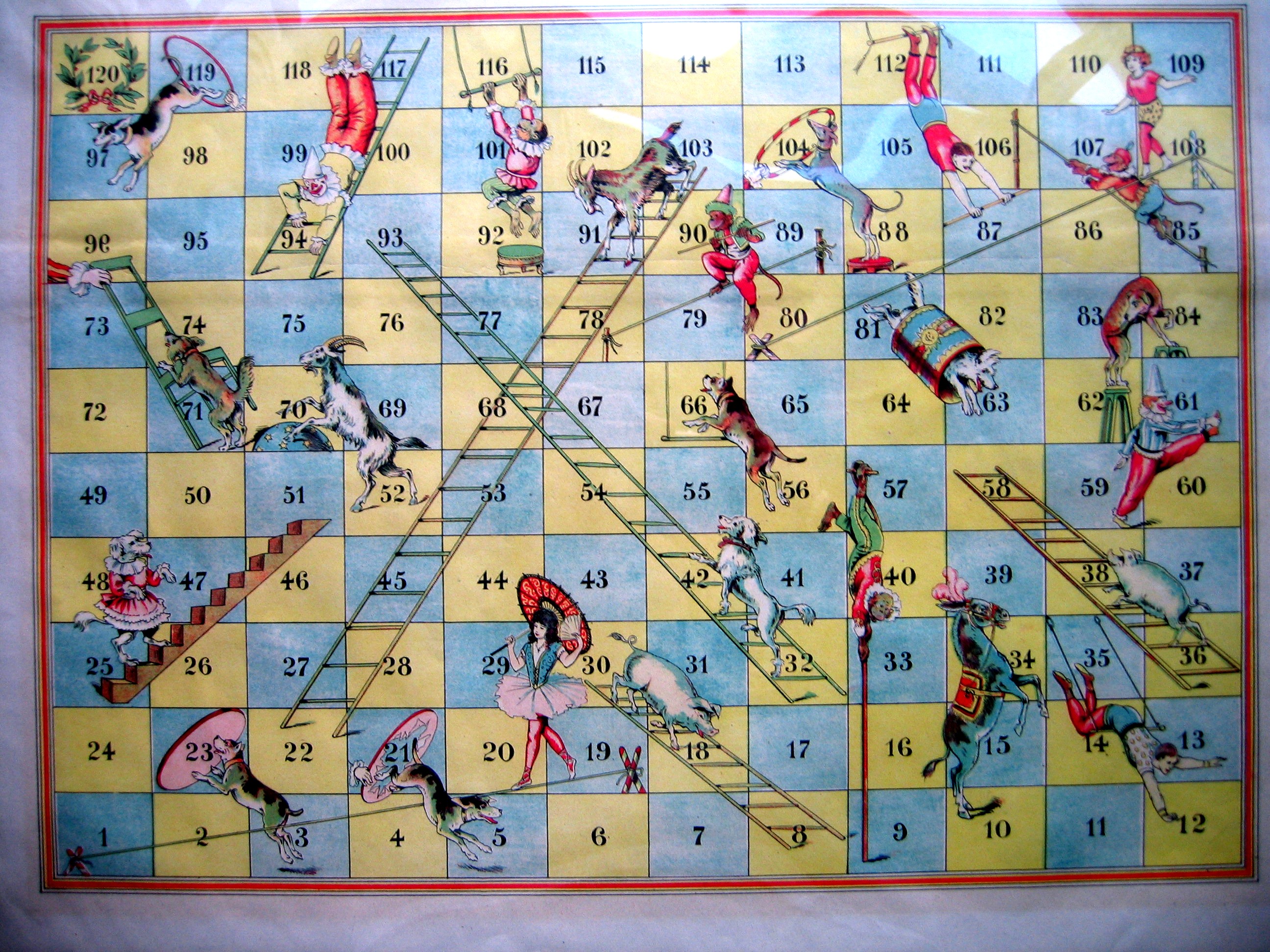

Nouveau Jeu du Cirque | |

| Primo autore: Non indicato | ||

| Secondo autore: Mauclair&Dacier | ||

| Anno: 1900/5 | ||

| Luogo: Francia | ||

| Periodo: XX secolo (1°/4) | ||

| Numero di catalogo: 430 | ||

| Percorso: Gioco di 120 caselle numerate | ||

| Materiale: carta (paper) (papier) | ||

| Dimensioni: 455X560 | ||

| Stampa: Litografia a colori | ||

| Luogo acquisto: Italia-Lucca | ||

| Data acquisto: 20-10-1984 | ||

| Dimensioni confezione: | ||

| Numero caselle: 120 | ||

| Categoria: Spettacoli, teatro, cinema, musica, circo, televisione | ||

| Tipo di gioco: Snakes and ladders | ||

| Editore: Mauclair-Dacier, Editeur, Paris | ||

| Stampatore: Non indicato | ||

| Proprietario: Collezione L. Ciompi - A. Seville | ||

| Autore delle foto: A. Seville - L. Ciompi | ||

|

Descrizione:

Gioco di 120 caselle numerate con tema il Circo. Analogo esemplare non colorato realizzato da "S. C. Paris" (400X520) ed un altro segnalato da A. Rabussier, firmato Ludovic e realizzato da Mauclair&Dacier. REGOLE: non riportate sul tavoliere. CASELLE: mute. NOTA: Scale e serpenti è un gioco da tavolo tradizionale, nato in Inghilterra e diffuso soprattutto nei paesi di lingua inglese (il nome originale è snakes and ladders). Si tratta di un semplicissimo gioco di percorso piuttosto simile al gioco dell'oca. Come nel gioco dell'oca, l'esito di una partita è completamente determinato dal lancio dei dadi. Tabellone e regole Il tabellone tradizionale di "scale e serpenti" rappresenta un percorso di forma bustrofedica, solitamente costituito da 10 righe di 10 caselle. Il percorso è reso più complesso da un certo numero di "scale" e "serpenti" che attraversano il tabellone verticalmente, congiungendo due caselle di righe diverse. La posizione delle scale e dei serpenti può variare. Analogamente a quanto avviene nel gioco dell'oca, i giocatori procedono del numero di caselle indicato dal lancio di un dado. Un segnalino che arriva in una casella posta "ai piedi" di una scala viene spostato alla casella in cima alla scala; viceversa, un segnalino che arriva in una casella con la bocca di un serpente "retrocede" fino alla coda. Nella maggior parte delle versioni, un giocatore che lancia un 6 ha diritto a giocare ancora. Vince chi arriva per primo all'ultima casella del percorso. In alcune varianti (non sempre), l'ultima casella deve essere raggiunta con un lancio di dado esatto; eventuali punti in eccesso porterebbero il segnalino a raggiungere la meta per poi retrocedere dei punti residui. La forma moderna del gioco fu inventata nell'Inghilterra vittoriana da John Jaques II della celebre casa editrice di giochi Jaques of London. Secondo alcuni, il gioco si dovrebbe considerare un adattamento di un antico gioco indiano chiamato dasapada; questa tesi è controversa. Il termine dasapada, in sanscrito, si riferisce a una griglia 10x10 e viene usato oggi soprattutto in riferimento a una variante degli scacchi. In ogni caso, John Jaques II era certamente un conoscitore dei giochi indiani; dal Pachisi, infatti, trasse l'idea per un altro suo grande successo, il Ludo. L'edizione del gioco più diffusa negli Stati Uniti si chiama Chutes and Ladders ("scivoli e scale") e fu prodotta da Milton Bradley. Anziché con un dado, l'entità degli spostamenti viene decisa con uno spinner. La grafica del gioco è ispirata ai campo giochi (le scale sono quelle degli scivoli, che svolgono anche il ruolo di "serpenti"). La versione più diffusa in Inghilterra è del tutto tradizionale ed è edita da Spear's Games. Exhibitions - "Le Jeu de l’Oie au Musée du Jouet". (Catalogo a cura di Jeanne Damamme - Pascal Pontremoli, pag. 80). Musée du Jouet, Ville de Poissy, 23 mars - 1.er octobre 2000. |

||

| Bibliografia:

1) AYALA García, Patricia - CARRANZA Flores, Antonio - NICOLINI Pimazzoni, Davide: "Serpientes y escaleras. Lecciones de expresión creativa y pautas de narrativa gráfica" ARTSEDUCA Núm. 9, septiembre de 2014. (Universidad de Colima, México, 2014). 2) SCHMIDT-MADSEN, JACOB: "The Game of Knowledge: Playing at Spiritual Liberation in 18th- and 19th-Century Western India". Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet, 2019. 3) Catalogo Mostra: “Le Jeu de l’Oie au Musée du Jouet”, Ville de Poissy, (pag. 80), 2000. |

||

| Snakes and ladders | ||

| Commento: Snakes and ladders, or Chutes and ladders, is a classic children's board game. It is played between 2 or more players on a playing board with numbered grid squares. On certain squares on the grid are drawn a number of "ladders" connecting two squares together, and a number of "snakes" or "chutes" also connecting squares together. The size of the grid (most commonly 8×8, 10×10 or 12×12) varies from board to board, as does the exact arrangement of the chutes and the ladders: both of these may affect the duration of game play. As a result, the game can be represented as a state absorbing Markov chain. The game was sold as Snakes and ladders in England before Milton Bradley introduced the basic concept in the United States as Chutes and ladders, an "improved new version of ... England's famous indoor sport." Its simplicity and the see-sawing nature of the contest make it popular with younger children, but the lack of any skill component in the game makes it less appealing for older players. History Snakes and Ladders originated in India as a game based on morality called Vaikuntapaali or Paramapada Sopanam (the ladder to salvation). This game made its way to England, and was eventually introduced in the United States of America by game pioneer Milton Bradley in 1943. The game was played widely in ancient India by the name of Moksha Patamu, the earliest known Jain version Gyanbazi dating back to 16th century. The game was called "Leela" - and reflected the Hinduism consciousness around everyday life. Impressed by the ideals behind the game, a newer version was introduced in Victorian England in 1892, possibly by John Jacques of Jacques of London. Moksha Patamu was perhaps invented by Hindu spiritual teachers to teach children about the effects of good deeds as opposed to bad deeds. The ladders represented virtues such as generosity, faith, humility, etc., and the snakes represented vices such as lust, anger, murder, theft, etc. The moral of the game was that a person can attain salvation (Moksha) through performing good deeds whereas by doing evil one takes rebirth in lower forms of life (Patamu). The number of ladders was less than the number of snakes as a reminder that treading the path of good is very difficult compared to committing sins. Presumably the number "100" represented Moksha (Salvation). Playing Each player starts with a token in the starting square (usually the "1" grid square in the bottom left corner, or simply, the imaginary space beside the "1" grid square) and takes turns to roll a single die to move the token by the number of squares indicated by the die roll, following a fixed route marked on the gameboard which usually follows a boustrophedon (ox-plow) track from the bottom to the top of the playing area, passing once through every square. If, on completion of this move, they land on the lower-numbered end of the squares with a "ladder", they can move their token up to the higher-numbered square. If they land on the higher-numbered square of a pair with a "snake" (or chute), they must move their token down to the lower-numbered square. A player who rolls a 6 with their die may, after moving, immediately take another turn; otherwise, the play passes to the next player in turn. If a player rolls three 6s on the die, they return to the beginning of the game and may not move until they roll another 6. The winner is the player whose token first reaches the last square of the track. A variation exists where a player must roll the exact number to reach the final square (hence winning). Depending on the particular variation, if the roll of the die is too large the token remains where it is. Specific editions The most widely known edition of Snakes and Ladders in the United States is Chutes and Ladders from Milton Bradley (which was purchased by the game's current distributor Hasbro). It is played on a 10×10 board, and players advance their pieces according to a spinner rather than a die. The theme of the board design is playground equipment--children climb ladders to go down chutes. The artwork on the board teaches a morality lesson, the squares on the bottom of the ladders show a child doing a good or sensible deed and at the top of the ladder there is an image of the child enjoying the reward. At the top of the chutes, there are pictures of children engaging in mischievous or foolish behavior and the images on the bottom show the child suffering the consequences. There have also been many pop culture versions of the game produced in recent years, with graphics featuring such characters as Dora the Explorer and SpongeBob SquarePants. In Canada the game has been traditionally sold as Snakes and Ladders, and produced by the Canada Games Company. Several Canadian specific versions have been produced over the years, including version substituting Toboggan runs for the snakes. With the demise of the Canada Games Company, Chutes and Ladders produced by Milton Bradley/Hasbro has been gaining in popularity. The most common in the United Kingdom is Spear's Games' edition of Snakes and Ladders, played on a 10x10 board where a single die is used. During the early 1990s in South Africa, Chutes and Ladders games made from cardboard were distributed on the back of egg boxes as part of a promotion. Mathematics of the game Any version of Snakes and Ladders can be represented exactly as a Markov chain, since from any square the odds of moving to any other square are fixed and independent of any previous game history. The Milton Bradley version of Chutes and Ladders has 100 squares, with 19 chutes and ladders. A player will need an average of 39.6 spins to move from the starting point, which is off the board, to square 100. The game can be won in as few as 7 rolls. In the book Winning Ways the authors show how to treat Snakes and Ladders as an impartial game in combinatorial game theory even though it is very far from a natural fit to this category. To this end they make a few rule changes such as allowing any player to move any counter any number of spaces, and declaring the winner to be the one who gets the last counter home. It is hard to deny that this version, which they call Adders-and-Ladders, involves more skill than does the original game. | ||

| Commento: | ||

| Commento: | ||